We want the nation’s children to be taught by teachers who are passionate experts in the subject they teach. There is widespread concern that many children are taught science and maths by teachers without an academic degree in the subject. This shortage is most acutely felt in physics, with large numbers of unfilled teacher training places, despite the offer of substantial financial incentives to train, and where a Department for Education survey reports one third of physics teachers do not have a degree in the subject.

Are we really sure that we want more graduates with a physics degree in the classroom? What types of careers should they forgo to do so and at what costs to the industries they currently serve? Central to these important policy discussions must be the demonstration that teachers with a physics degree are more effective in delivering the GCSE curriculum than those who simply have an A-Level.

In this piece, we use the School Workforce Census to explore where teachers with a physics (or engineering) academic degree are currently teaching. Although theoretically a census of all schools, only about a third of secondary schools have completed the qualifications and curriculum parts sufficiently well for us to feel confident in using the information. In these schools we focus on the teachers who report they are teaching Key Stage Four science classes in 2013.

In this sample of 1128 secondary schools, about 45% of all GCSE science teaching time appears to be with somebody who doesn’t have a science first degree (or Masters or PhD), using Department for Education mapping of degree subject to curriculum area. We find just 10% of Key Stage Four teaching time is with a teacher who has a physics or related engineering degree. For comparison, the Institute of Physics survey claims fewer than 1 in 5 science teachers have a specialist physics degree and a Department for Education survey says one third of physics teachers do not have a degree in the subject. In our sample, as many as 40% of schools are delivering their Key Stage Four curriculum without a teacher with a physics degree on the teaching team.

Schools with a higher attainment pupil intake have more physics specialist teachers

We first look at the kind of schools that have greater numbers of science and physics specialists delivering the Key Stage Four science curriculum. Perhaps not surprisingly, they are more prevalent in schools with a higher entry attainment of pupils.

The location of teachers with physics and science degrees by ability of pupil intake

The more specialist physics teachers you have, the more students take GCSE Physics, but which is the direction of causation here?

Schools will vary a great deal in how many students are encouraged to take the ‘triple sciences’ GCSEs of biology, chemistry and physics, rather than a double or single-award science. We explore this by grouping schools into whether they have (i) no teachers claiming to have a physics degree in their Key Stage Four teaching team, (ii) up to 20% of teaching time with a teacher who has a physics degree, or (iii) over 20% of teaching time with a teacher who has a physics degree.

There is some evidence that schools with larger numbers of physics specialists have slightly higher entry rates to GCSE Physics – two and five percentage point higher entry rates for modest and high numbers of physics specialists, respectively (holding constant entry attainment at school).

However, it is not obvious which comes first. Do specialist physics teachers encourage GCSE Physics take-up, or do high triple-science entry levels attract specialist physics teachers to apply to teach at the school and does the school need to work harder to recruit them?

Proportions taking GCSE Physics by entry attainment of school intake

There is no relationship between having physics specialists and GCSE outcomes in science or physics

We cannot look at the effectiveness of a department’s teaching by observing their GCSE Physics grades because not everyone takes the subject. Instead, we look for any relationship between the presence of Key Stage Four teachers with a physics degree and GCSE attainment in two ways.

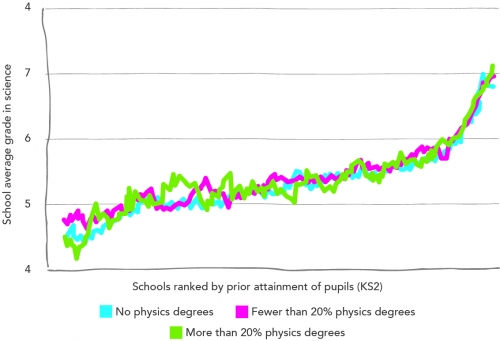

First, we look at whether the Key Stage Four teams that are well-endowed with physics specialists have a higher average point score in science, controlling for entry attainment. We find no such relationship. Obviously a pupil’s science point score can be achieved through a variety of different qualifications and so it isn’t an ideal measure of teaching quality or pupil mastery of physics.

School average point score in pupil’s best Science GCSE

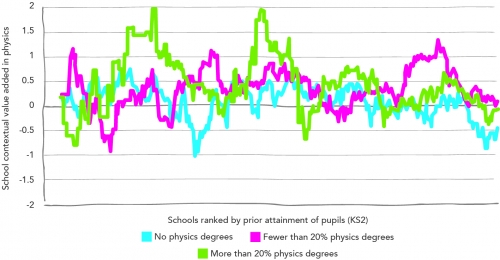

Second, we use a physics contextual value-added score to assess performance, taking into account all prior attainment and pupil demographic characteristics that we can observe. It is constructed to have a mean of zero, even though more able pupils are more likely to take GCSE Physics. Once again, there is no overall relationship between school physics CVA and the number of physics specialists in the school, either on average or for any particular type of school.

Physics contextual value-added score also appears to be unrelated to teaching by specialists

Given the undeniable shortage of teachers with a physics degree delivering the science curriculum (note – in our sample, 25% of those with a physics degree report they are teaching maths), schools face the very real trade-offs about how to manage. Can they really cope with offering GCSE Physics to most of their pupils? And if they are hiring new staff, should they favour the biologist who performs outstandingly well at interview or a physicist to rebalance the science teaching team?

All our intuitions tell us that teachers with physics degrees should be better at teaching physics than those without. This is akin to saying that teachers with the greatest mastery of the subject should be the greatest teachers. Once we generalise to this level, we can draw on the wealth of evidence that suggests teacher quality appears to be largely unrelated to academic credentials. It is a surprising and little understood finding – it seems that the ability to engage and impart knowledge is quite a different skill than the ability to understand and store information yourself. With this in mind, why should physics teaching be any different?

This analysis is consistent with a wealth of US research and our own findings at Teach First. We recruit a number of participants to Teach First without a degree in the subject they’ll be teaching – as long as they have an A-Level in the subject and pass a knowledge assessment – and have never found any difference between these recruits and others on our quality measures (e.g. QTS score, likelihood to drop out).

It’s not really that surprising. The type of content that a physics undergraduate deals with is very different from that on the GCSE syllabus. It does not mean, though, that academic ability doesn’t matter in teacher selection. US research by Rockoff et al. shows that teachers’ scores on cognitive tests can be modestly predictive of pupil outcomes.

Nor does it mean that subject knowledge doesn’t matter. Heather Hill’s research on Knowledge For Teaching shows a strong relationship between teachers’ ability to explain mathematical concepts and predict students’ misconceptions and those students’ outcomes. Perhaps teacher training needs to focus more on translating ITT recruits’ existing knowledge into ‘knowledge for teaching’?

Sam Freedman, Director of Research, Evaluation and Impact, Teach First

Is high GCSE attainment what defines ‘good’ in physics teaching? Evidence from PISA 2006 suggests that internationally there is an inverse relationship between attainment and interest in science. In countries with the lowest science attainment (typically less developed countries like Mexico and Brazil), students show high interest in science, while in countries with the highest attainment (like Finland and Netherlands) students show low interest. There are several possible explanations for this effect, but one thing is for sure: there are many ways teachers can get high GCSE attainment, and not all of them are inspiring nor encourage to progression to A level study. For a subject like physics, where demand for qualified physicists exceeds supply, it is arguable that inspiring teaching is even more important than teaching that gets high GCSE scores.

Sir John Holman, Senior Adviser in Education, The Wellcome Trust

Leave A Comment