I recently watched the recent BBC series ‘Are Our Kids Tough Enough: Chinese School’ which followed the experiences of five maths teachers from China as they started teaching in a school in Southampton. I anticipated that I might learn something that might explain the very high levels of attainment of students from China in international tests, such as PISA. The series did, as expected, play on the cultural differences between England and China. It wasn’t clear, however, that different approaches to teaching could explain why students in China have higher levels of maths attainment than those in England. What the series did serve to highlight therefore was the increasing influence that the results of international assessments are having on education policy.

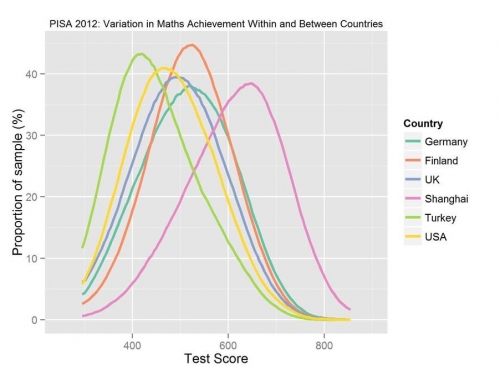

The main reason for the increasing influence of international assessments on education policy is due to the size of the gap in attainment between students from Far Eastern countries, but particularly those from the Chinese provinces of Shanghai and Taipei, and western countries. The difference in the level of attainment of students in Shanghai and western countries are truly staggering. The Figure below shows the distribution of test scores for maths from the 2012 PISA survey for Shanghai and OECD countries with both relatively low (Turkey) and relatively high (Finland) levels of attainment. The figure shows that the mean score for students from Shanghai (610 points) is around 100 points higher than the scores for students in most western countries. PISA maths test scores are normed to have a mean of 500 points and a standard deviation of 100 points. In international assessments the expected growth in attainment for one year of schooling is usually estimated to be about 0.30 standard deviations. The differences in attainment between Shanghai and western European countries are therefore equivalent to significantly more than two years of schooling.

It is important to point out, however, that although policy makers have looked to the characteristics of the education system in Shanghai to explain the countries performance, the different character of countries in terms of culture, history and populations makes it very difficult to draw any conclusions concerning the causal effects that education systems have on performance. It is difficult to dispute the evidence from PISA that students in Shanghai have higher levels of attainment than those in western countries. What is at issue is the validity of the conclusions about the causal link between schooling and attainment and the implications for education policy. The outcomes attributed to schooling may simply reflect differences in national contexts and other factors which make children in Shanghai different from those in western countries. For example, the figure below shows the level of involvement in various activities related to maths reported by students in Shanghai, Taipei and the UK as part of the 2012 PISA survey. The figure shows that, in comparison to the UK, young people in Shanghai spend more of their time outside school doing maths and activities such as chess. The differences in attainment in PISA may therefore not be entirely to do with the characteristics of education systems in the different countries but rather a range of factors may be involved.

In addition to differences in contexts another reason for being cautious about attributing differences in countries performance to features of the educations systems is the relatively small proportion of the total variation in test scores that occurs between countries. For example in the figure above the mean test scores for Germany, the UK, Finland and the USA all fall in a relatively narrow band between 480 and 520 points. In comparison, the variation in test scores between students with low and high levels of attainment in each country is over 200 points. The high proportion of the total variation in attainment that is between students within a country suggests that the main factors influencing student attainment are located within rather than between countries. I am not suggesting that we should not try to learn from the education systems in other countries but exchange programmes involving teachers from Shanghai, such as that recently announced by the Department of Education (https://www.gov.uk/government/news/elite-teachers-travel-from-shanghai-for-pioneering-maths-exchange), are unlikely to provide a solution to the problem of low attainment for a high proportion of children in the UK.

Leave A Comment