Today at Mulberry School for Girls in east London (one of my PGCE placement schools well over a decade ago), headteachers and policy makers are coming together to consider how we can address the gender imbalance in headship in our schools.

Not everyone agrees there is a problem that needs to be solved. As Andrew Old (@oldandrewuk) regularly points out on twitter, the majority of headteachers are women. But the chances of a woman teacher making it to headship is far lower than that of a man. To illustrate the problem, if we walk into a school chosen at random and pluck out the first man and first woman that we see, it is 2-3 times more likely that the man rather than the woman is the headteacher.

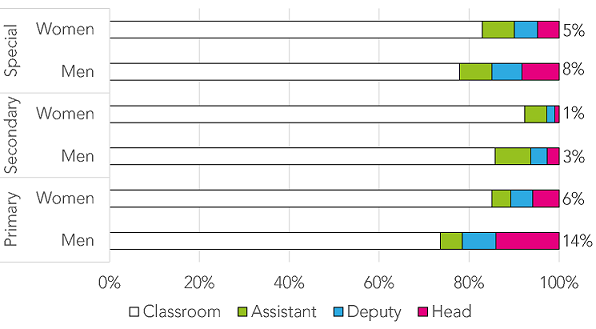

Men are far more likely to make it to headship

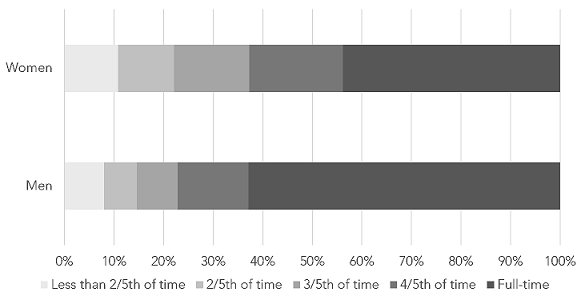

Across all industries, women’s careers are more likely to be interrupted by child rearing. The chart below shows what proportion of time women and men teachers were working over the past five years (according to the School Workforce Census). 63% of men worked full-time in each of the five years versus 44% of women. The rest are working part-time or taking a career break at some point. Policies to support all teachers who need to work flexibly are important, because they will increase retention. If they are successful, they will disproportionately benefit women.

Women are more likely to work part-time and take career breaks

Note: chart excludes teachers aged 56 and over in 2010 to avoid retirement

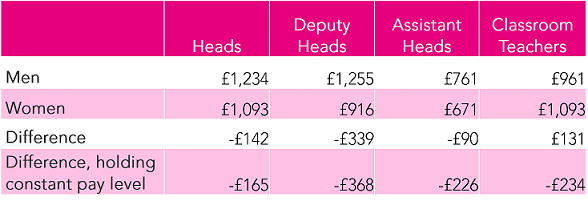

We have published analysis before to show that women working full-time achieve a smaller annual pay rise than men, especially once they reach the Senior Leadership Team. (This is also true when controlling for initial level of pay, age of teacher, tenure at school and region.)

Annual pay rises achieve by full-time workers

Note: this compares wages between 2010 and 2011

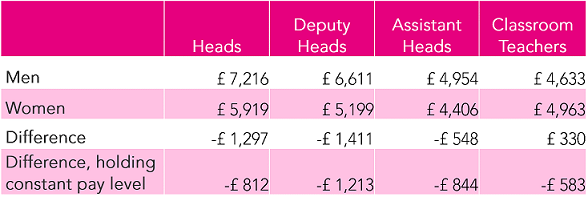

In the table below we show the pay rises over four years achieved by women and men who worked full-time from 2010 to 2014. The pattern of women’s pay falling behind, even where they work full-time, is still present.

Pay rises achieved over 4 years between 2010 and 2014

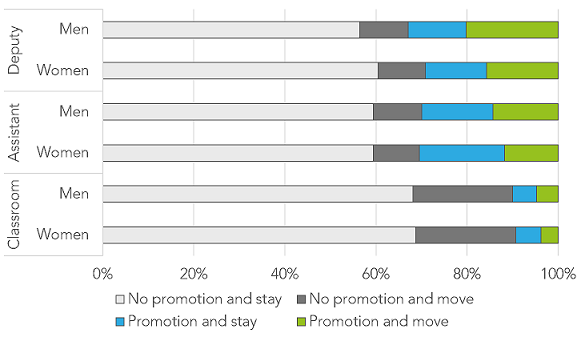

Pay rises can be achieved by staying in post, moving school and/or gaining promotion. One reason why women may achieve lower pay rises is they are less likely to achieve promotion. In the chart below, the rates of promotion and school move are shown for full-time teachers over a four year period. Women are a little more likely to achieve internal promotion to head within the same school, but are less likely to be promoted to a different school (in the same region or in another region – not shown here). They may feel less confident that they are ready to seek promotion to headship or may have other life commitments that mean they feel unable to take it on. They may feel highly geographically constrained by a spouse job or childcare arrangements. Alternatively, selection panels may frequently have an unconscious bias towards a male candidate when they are previously unknown to the school.

Rates of school moves and promotions between 2010 and 2014 for full-time teachers

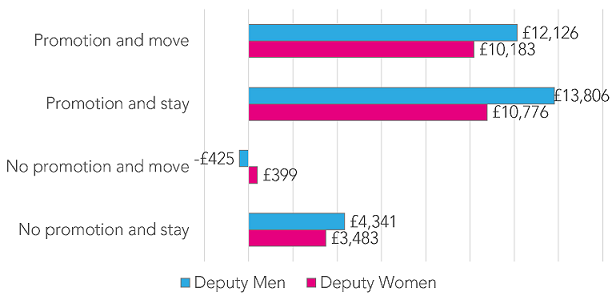

While women who work full-time are somewhat falling behind in their rates of promotion from deputy to headship, more importantly, the pay rises they achieve with these moves appear to be lower. This is particularly true for internal promotions to first headship in secondary schools. Men actually see a greater wage fall if they decide to make a sideways move to a deputy head post at a new school – these moves may be forced by household relocations and some of this wage fall is explained by loss of London weighting. But even for those remaining as a deputy head within the same school, the wage rise advantage of men remains. All these patterns hold if we control for the teachers’ initial pay, age, tenure in school and region.

The apparent wage bargaining advantage for men is much stronger in secondary schools than in primary schools. We cannot show why this is. It may be explained by greater wage variation overall for secondary headteachers or result from lower levels of guidance in wage setting from local authorities. Or it may simply be that men receive these higher wages in return for the types of roles they take on, whether they be more complex schools or risky headships of previously underperforming schools.

Four year pay rises associated with different types of job moves for deputies in 2010 who worked full-time throughout

I hope this analysis helps give those at the Summit today a framework for talking about how to support women to headship.

Leave A Comment