Over the last two decades, the number of young people in England getting a degree has risen sharply: up from around 10 per cent as recently as the 1990s, to more than 30 per cent today.

This expansion has led to concerns being expressed in some quarters that not all young people who get a degree may have the level of achievement needed to do well afterwards. A recent example came in a report from the OECD, which used data from the PIAAC survey of adult skills to argue that around one in ten graduates in England had low basic skills.

The report concluded that for this group, going to university was inefficient and represented a waste of resources both for the government and for themselves. Instead these resources should be diverted into further education, the OECD said.

So what does the PIACC data show?

Measuring adult literacy

The PIAAC survey collected data on adult skills in a range of countries between 2012 and 2014, following the methodology used by the earlier International Adult Literacy Survey (IALS).

PIACC differs from IALS in some ways – only covering a proportion of the items that IALS used to measure adult literacy, for example, but including the ability to understand information from electronic texts.

The information collected by the surveys is broadly comparable, though, and rescaling IALs results to the same 0-to-500 scale on which PIACC adult literacy results are recorded allows for an examination of whether the rise in the number of young people going to university has been associated with a decline in the skills of graduates over time.

Comparing IALS and PIACC results

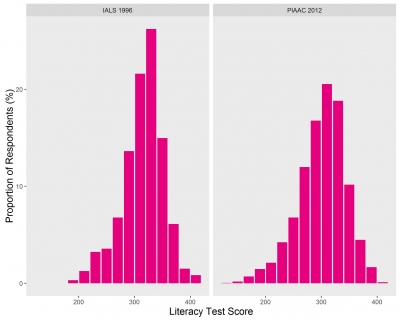

The figure below shows the distribution of literacy test scores for young adults in England with a degree in the 1996 IALS and 2012 PIACC [1] surveys.

This shows that the proportion achieving high test scores in 2012 was lower than was the case in 1996.

For example, 21.6 per cent of young adults with a degree who took part in the 1996 IALS survey achieved scores of between 300-320 points, but only 20.5 per cent had scores in the same range in the 2012 PIACC survey. For scores in the range 320-340 points, the drop was from 26.2 per cent to 18.8 per cent.

The results do, therefore, suggest that there’s been a decline in the literacy skills of young graduates in England – although, of course, their skills may have increased in areas not measured by the surveys.

Over this period, the IALS and PIACC data record an increase in the share of those aged 20 to 34 who have a degree; from 10.5 per cent of young adults in 1996, to 30.0 per cent in 2012.

Literacy test scores in graduates in England aged 20 to 34, 1996 IALS versus 2012 PIACC

Taking an international view

We might also wonder how the change in test scores has varied across countries.

International comparisons can be helpful in cases such as this, as they allow us to gain an insight into the role of factors such as workplace training or the nature of schooling that don’t vary to a great extent within a single country.

One thing to note, firstly, is that the proportion of young adults who enter higher education varies by country. In every country that participated in both IALS and PIAAC, however, there was a significant increase between 1996 and 2012 in the proportion of young adults who gained a degree. The largest of these increases were in England, Finland and Northern Ireland, which all saw rises of more than 20 percentage points.

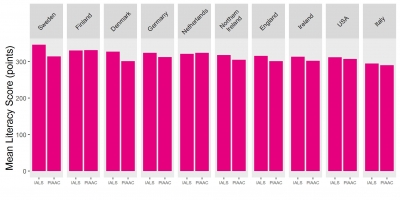

When we look at the mean literacy scores for young adults with degrees in 1996 IALS and 2012 PIACC[1], a number of interesting results emerge.

In most countries, mean literacy scores were lower in the 2012 survey – with the effect that countries’ relative positions changed little over this period.

In Sweden and Denmark, however, the fall in scores was markedly greater than in other countries – while Finland and the Netherlands actually saw a slight increase in test scores over time.

Mean literacy score by country, 1996 IALS versus 2012 PIACC

Lessons for policymakers

So what is the upshot of all of this?

For one thing, the variation in results shows that an increase in higher education participation doesn’t inevitably lead to a decline in the basic skills of graduates.

Secondly, there are lessons that can be taken from Finland.

Finland is routinely the highest performing western country in international tests of children’s achievement such as PISA.

These skills surveys show that, between 1996 and 2012, the country had one of the largest expansions of higher education in the west, as well as an increase in graduate literacy scores.

This suggests that the quality of schools in different countries is an important factor influencing the impact which a rise in university participation has on basic skill levels among the graduate workforce.

Although in the UK the government has recently issued a green paper with proposals to improve teaching in universities, differences in the skill levels of graduates would seem to largely reflect inequalities that are inherited from the school system. School reforms aimed at raising the achievement of all children seem necessary if we are to significantly increase the skills of young people leaving university.

1. IALS and PIACC surveys were undertaken in slightly different years in different countries. For simplicity, all results are referred to here as stemming from either 1996 or 2012.

Leave A Comment