The starkest figure published in last week’s Key Stage 4 statistical first release (SFR) was the Progress 8 score for Knowsley, a small unitary authority in Merseyside. Pupils attending its six secondary schools achieved on average almost a grade per subject lower than pupils with similar prior attainment elsewhere in the country. All six schools were provisionally below the floor standard of -0.5 (the official list of schools below the floor will be published with Performance Tables in January).

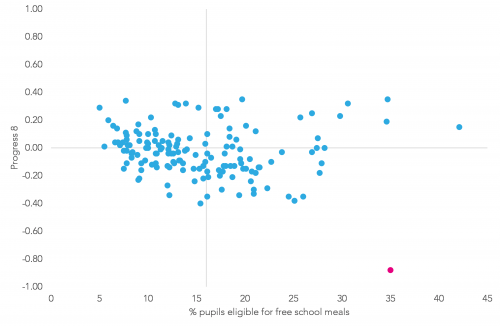

Progress 8 by local authority, 2016

Knowsley is unusual in that it is extremely deprived. 35% of pupils were known to be eligible for and claiming free school meals in January 2016, a figure unparalleled outside London.

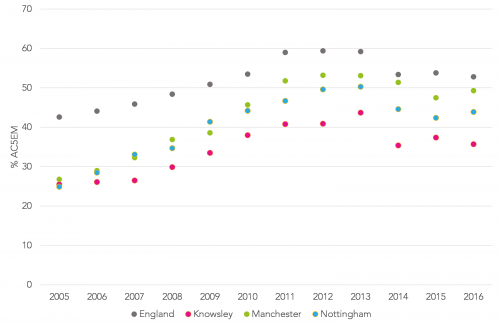

Attainment in the borough has historically been low. The chart below shows the percentage of pupils achieving 5 or more A*-C grades (or equivalent) including GCSE English and mathematics between 2005 and 2016. (Results fell nationally in 2014 following changes made to Performance Tables [PDF] following the Wolf Review.)

Percentage of pupils achieving 5 A*-C grades (or equivalent) including GCSE English and maths, 2004/5 to 2015/16

Manchester and Nottingham are also shown for no good reason other than that they had similar levels of a) free school meal eligibility and b) attainment in 2005. The gap to the national average has stubbornly persisted in Knowsley much more than in Manchester and Nottingham.

However, these latter two authorities had higher levels of pupils with a first language other than English in its secondary schools in 2005 (20 per cent and 10 per cent respectively) which further increased to 33% and 27% by 2016. By contrast, this figure increased from 0.3 per cent to 1.4 per cent in Knowsley over the same period.

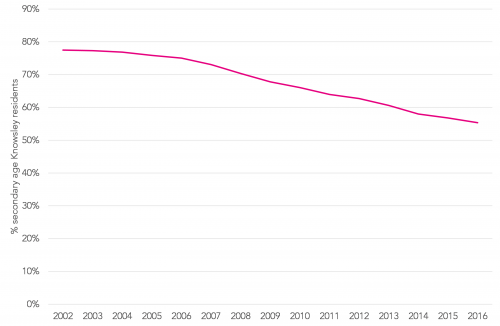

Knowsley is also unusual in that it is small, the number of children living there is falling and increasing proportions of secondary-age resident pupils are attending schools in other local authorities. The 2016 SFR on schools and pupils [XLS] shows that out of 8,200 resident pupils, just over 5,000 (55 per cent) go to school in the borough. This figure has fallen by 22 percentage points since 2002. There are just 500 pupils attending schools in the borough but resident elsewhere.

Percentage of resident secondary-age population attending schools in Knowsley, 2002-2016

Our own calculations suggest that residents who go to schools in other boroughs tend to be less deprived: 16 per cent were eligible for free school meals compared to 35 per cent who go to school in the borough in 2016.

A number of schools in the adjoining local authorities of Liverpool, Sefton and St Helens close to the border with Knowsley are also provisionally below the floor standards. If we were to arbitrarily draw our own set of local authority boundaries perhaps we might be able to create some areas of the country with lower attainment and progress than this part of Merseyside but not very many.

It can also be said that attainment has not improved in Knowsley for want of trying or want of funding. Most national initiatives over the last twenty years appear to have been tried. Excellence in Cities arrived in 1999. Five of its ten secondary schools were included in the National Challenge when launched in 2008. All ten secondary schools were transformed into seven new-build “centres for learning” in Wave 1 of Building Schools for the Future. Ofsted has inspected these establishments over 30 times since 2011, the last time any was rated good or better. Five are now rated less than good. A new sponsored academy replacing a special measures school is awaiting a first inspection. The other has closed outright.

Perhaps surprisingly though, academisation only arrived as recently as September 2013. The final community school converted to academy status in January 2016, dropping the “centre for learning” monicker in the process. Today, two of the six schools are sponsored academies, two are converter academies and two are voluntary aided.

Old Ofsted documents, such as inspection reports and annual performance assessments (APA) show that the inspectorate was positive about the local authority and its capacity to improve in the early part of the century. Reading the inspection report [PDF] of 2003, the inspectors were clearly impressed by the transformational strategy of the LA and the “powerful and visionary” leadership of its Director, judging it outstanding for capacity to improve.

The report also talks positively about an approach to teaching and learning called “mind-based learning”, which featured prominently in the authority’s improvement strategy and which is described further in a contemporaneous article from the Guardian. It is perhaps too easy to mock the belief in learning styles with the benefit of hindsight. We have no reason to doubt the motives of those involved. They may well have made the best decisions given the evidence available to them at the time. Do we necessarily have any better evidence now about raising attainment in a deprived area of northern England?

Perhaps working with sponsors will be the solution. Maybe there isn’t one, at least not one that will deliver sustainable improvement in the short to medium term. Would it be wrong to say that anyone who plays a part in raising attainment in this part of the world will have helped to solve the greatest challenge facing the education system in England?

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from Education Datalab? Follow Education Datalab on Twitter to get all of Datalab’s research as it comes out.

Isn’t Knowsley the only LA that doesn’t have any A levels available within its boundaries any more? I’m not saying that’s the cause of the poor outcomes at KS4, it’s more likely that it is as a result of the fact that few pupils get the GCSE grades they would need to go on to A levels … but it does then very likely become a vicious circle, where brighter pupils from more aspirational families, with an eye to A levels in the future, might choose an 11–18 school outside the LA. There are several good and outstanding 11–18 schools in Liverpool, Halton and St Helen’s that are close to the boundary, so it would be no surprise if these were attracting more able pupils.

This kind of entrenched underperformance is not something that can be tackled by schools alone. It needs a “beyond the school gates” type approach that works across the whole borough to improve the outcomes and life chances of adults as well as kids, and to look at the wider issues that are creating this downward spiral. Schools on their own can only do so much, and if kids’ lives are a total mess then they are simply not going to be in the right place to learn.

Hi Stephen. Thanks for commenting. I certainly agree with the second part though much appears to have been tried over the years yet the chronic under-performance persists. It does look like brighter pupils are tending to opt for schools in other boroughs- the prospect of A-level provision may be a factor. There is a 6th form college in Cronton just over the border in Halton so A-levels are readily available for those who can get to it easily.

I wish I knew.

I’ve worked in Knowsley as well as in the leafy suburbs. In my view, the constant stream of new initiatives is certainly detrimental. I believe that teachers in Knowsley work harder than many, putting in place strategies that have been crudely transplanted from ‘good’ schools in very different circumstances. It’s a scatter gun approach which is burdensome and often futile.

Retention of good staff and school leaders is sure to be a problem but, having worked with some great teachers in Knowsley and elsewhere, I don’t think there is a huge gulf in the inherent ability of these practitioners. It’s just a very difficult gig.

Attach a social worker to every tutor group???

… can’t see sponsorship working

I was working in Knowsley at the time of the so called ‘transformation’ through Building Schools for the Future and I undertook a case study of what was happening which I submitted for my Educational Doctorate at Liverpool John Moore’s University. At the time many academic journals would not publish my results, maybe for fear of upsetting the Government’s expensive whim. As an Education Action Zone, the individuals responsible for the Knowsley project were enabled to carry out their ideological dreams without opposition. I agree with previous commentators, I worked with a lot of dedicated and hard working teachers in Knowsley, who became demoralised and beaten into submission and left, because of poor management and ‘wacky’ ideas. Knowledgeable parents and staff were against the proposals, which resulted in the mass movement into neighbouring boroughs. The open-plan schools are a legacy of the so called ‘progressive’ educational movement, which are impossible to teach and learn in and difficult to manage, because of the constant traffic moving through these spaces. Until this is rectified these schools will remain unattractive to ‘positivist’ educators who recognise that a knowledge based curriculum is paramount for high performance, which then can lead to further and higher educational opportunities.