The Department for Education has published a consultation document on family incomes, pupil attainment and school attended that will either fascinate (if you are a data cruncher) or terrify you (if you are a privacy campaigner).

For the first time, the records of pupils sitting in the National Pupil Database have been matched to parental tax and benefit records (using child benefits as the link). So we are able to separate out the vast swathes of pupils who are never eligible for free school meals.

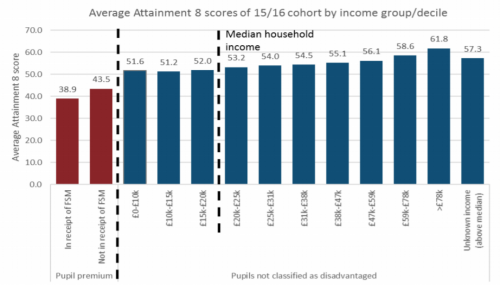

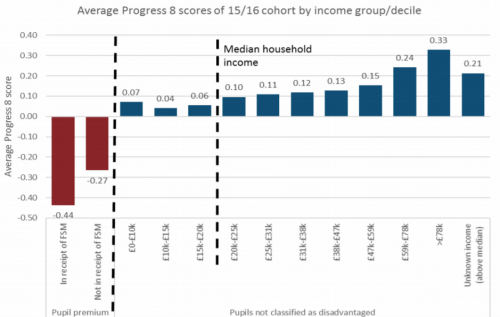

Pupil Premium and free school meals eligibility is an excellent proxy for educational disadvantage

This chart shows in red how poor the overall GCSE attainment of Pupil Premium children is. This will be a great comfort to politicians who have used it as a metric to divert vast sums of money to schools.

Those claiming benefits that entitle them to free school meals have a typical GCSE grade below a D. By contrast, all income groups of those in work have typical GCSE grades of a C or better.

And if we look at progress made during secondary school for those with similar age 11 starting points, those who have recently claimed benefits make almost half a grade per subject slower progress than others (a Progress 8 score of close to -0.5).

It is clear that the Pupil Premium group shouldn’t be extended to include ‘just about managing’ families

This government has posited the idea that the focus on Pupil Premium students ignored a large set of low income families who were also struggling to access high quality education for their children (the group previously referred to as those ‘just about managing’ – but the terminology seems to have switched to that of ‘ordinary working families’ in this latest consultation).

There are, of course, many pupils in all income groups with poor educational outcomes that are masked by the reporting of mean averages in these charts. But the charts do emphasise that we should not use household income to identify a group of lower earners who should also attract funding or preferential treatment in access to schools. As the charts above show, those who have not claimed benefits during secondary school typically do not have children who are struggling educationally, even if they themselves are on very low incomes.

The other interesting set of outliers in these charts are those children from families earning either £59-78,000 or over £78,000. These children really do perform significantly better than others, but I can’t imagine any government wishing to restrict their access to high quality schools in any way!

The flat relationship between household income and pupil achievement doesn’t mean anyone can make it

It would be easy to read these charts and conclude that, provided your family does not claim benefits, it is possible for anyone to succeed at school.

This wouldn’t be the right conclusion.

Household income generally isn’t found to be an important causal contributor to child’s attainment (see here and here). It is simply a relatively poor proxy for other important social factors that tell us how well a child is likely to do at school, including parental education (see here and here).

So within each of these income groupings, there are children coming from materially different home environments that will significantly affect how successful they will be at school.

If we want to create useful indicators that tell us how much the state should intervene to support a child at risk of falling behind at school then we’ll have to do better than simply matching in tax records to the National Pupil Database.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from Education Datalab? Sign up to our mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive our half-termly newsletter.

I really enjoyed the article but if we really want to create indicators of which children will fall behind we should identify those children whose first 36 months of life are in homes that produce ‘word poor’ environments. We perpetually waste £biĺlions on trying to improve secondary outcomes when the solution to the problem is 100% free.