Update, 24 May 2017, 13:14: Schools Week have reported that the Conservatives are distancing themselves from the £60m figure.

One of the more eye-catching proposals in the Conservatives’ manifesto was the plan to drop universal infant free schools meals (UIFSMs) and bring in free breakfasts for all primary pupils [PDF].

While no further details were given in the manifesto, a press release from the Conservatives said that ending the UIFSM policy would save £650m, which would be spent on other priorities in education. Free breakfasts would cost £60m, it said.

That £60m figure looks very optimistic.

Where does the £60m cost come from?

No further details have been provided on how the £60m figure has been reached, but it appears to have been reached using figures from the Education Endowment Foundation’s evaluation of a scheme called Magic Breakfast, which provides free breakfasts in schools serving deprived areas. (The evaluation found that the programme improved children’s attainment and behaviour.)

According to the evaluation, average non-staffing costs were £11.86 per pupil per year [PDF], most of which related to food, and staffing costs averaged £5.46 per pupil per year.

There were 3.7m children of compulsory school age enrolled at state, mainstream primary schools in January 2016, the latest figures available.

So a non-staff cost of £11.86 per pupil per year would lead to a total annual figure of £43.4m, with an average £5.46 figure for staff costs leading to a total figure of £20.0m – bringing the total to around £63m.

But there are a couple of crucial things we need to bear in mind when working with the figures from the Magic Breakfast evaluation.

Take-up

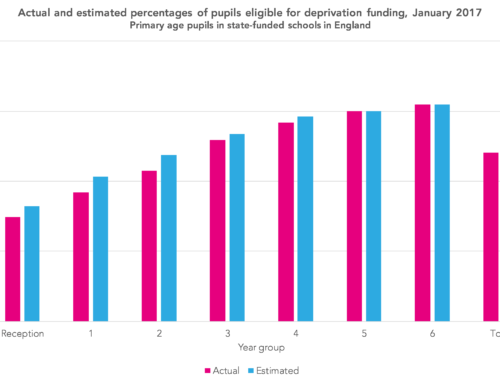

Firstly, the evaluation states that cost figures are an average across all pupils enrolled in the schools that took part in the study [PDF] – but that only 23.6% of the sample actually took up the offer of a free breakfast [PDF].

It seems like the Conservatives’ cost figure is implicitly based on take-up at this level, then.

Take-up is certainly sure to be some way less than 100% – the offer of a free breakfast won’t alone be enough of an incentive to persuade some families to change their morning routine, and stop having breakfast as a family.

And there are reasons to think that schools that participated in the Magic Breakfast trial might have higher take-up than other schools. These schools had high levels of pupils eligible for free school meals, so it seems reasonable to think there might have been more demand for a free breakfast.

But provision of a breakfast before regular school hours might be looked at by some in another way – as a substitute for morning childcare. This would suggest that take-up might actually be highest in areas where parents already currently pay for morning childcare.

While the Magic Breakfast trial ran for an academic year, it’s also the case that parents take some time to switch from existing provision to use of a school service, which may mean the rate seen in the evaluation is lower than that which would be reached if the policy is brought in nationally.

Staffing

The staffing element of the costs from the Magic Breakfast evaluation also seem very low.

The average cost is given as £5.46 per pupil per year. But if this were the case nationally, at £5.46 per pupil per year, with 3.7m pupils across nearly 17,000 state, mainstream primary schools and 190 school days per year, that would translate to each school spending just £6.26 per day on staffing.

The Magic Breakfast evaluation also reports that schools on average recorded using 700 hours from teaching and support staff (teachers, teaching assistants and support staff) and 100 hours from volunteers per year to deliver the programme.

This translates to 3.7 hours of staff time per school per day, which seems hard to reconcile with the cost figure. It may have been possible for some schools to ask existing staff to work different hours to cover the provision without increasing their wage bill. But this approach simply isn’t feasible in a mandatory programme where budgets are already stretched and teaching assistant numbers have been drastically reduced in some schools.

Building an estimate from scratch

So what do we think the actual cost might be?

A number of assumptions are required, but it’s still possible to come up with figures that let us get to grip with the question.

Key assumptions that we’re going to use are that:

- the breakfasts are delivered in an hour-long breakfast club before the start of the school day (including set-up and cleaning time);

- the cost per pupil of food is 25p. This seems to be roughly the cost that the Magic Breakfast evaluation assumes;

- a staff-pupil ratio of 15:1 is used. This is lower than the staffing ratio which appears to have been in place in the schools in the Magic Breakfast evaluation;

- breakfast clubs are predominantly delivered by teaching assistants or support staff, who have to be employed for an extra hour each day, at a cost of £15 per hour (total cost to the school);

- take-up of free breakfasts is 20%.

Combining these factors suggests a total cost of £174m per year, translating to around £1.25 per pupil who takes up a free breakfast per day. Clearly this is well above the £60m figure in the Conservatives’ costing.

The take-up rate of 20% is lower than the 23.6% in the Magic Breakfast evaluation, and is probably the single greatest uncertainty in the calculation. The chart below shows how the cost varies with different levels of take-up, with all other assumptions kept the same.

Other factors

There are a number of ways in which the policy could be implemented which could lead to radically different cost figures – some of which schools may find they need to consider out of necessity.

If the service was delivered largely by volunteers that would take out most or all of the staff costs – though how feasible this is is debatable.

If schools served breakfasts as part of the morning session, as in done in some places, that could potentially mean there were no additional staff costs – but with the clear costs of disruption to the school day and lost teaching time. Take-up would also go up to near 100%, so there would be a corresponding increase in food costs.

Alternatively, there might be a way in which the breakfasts themselves could be offered for free, but with a charge to attend the before-school breakfast club in which they are served, except for those eligible for free school meals. Perhaps, though this is maybe straying into the realms of the far-fetched.

The other alternative

If heads aren’t given enough money to serve free breakfasts, they’ll – against their natural instincts – be incentivised to make the breakfasts as undesirable as possible: bad food, served in a 15-minute window before the start of the day.

That might allow a Conservative government to say that it had delivered on its manifesto pledge, but it would rather undermine the point of the policy.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from Education Datalab? Sign up to our mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive our half-termly newsletter.

I’ve asked some primary heads how much they think it would cost to deliver a universal breakfast to children. Overall, their responses confirm that our estimates are reasonable guesses.

Per hour costs of staff:

Outside London it is possible to employ midday staff for about £9ph (with on-costs). However, kitchen staff cost more than £15ph and the minimum wage is rising. We therefore think the £15ph estimate is sound.

Staff-pupil ratios:

There are a range of responses about this. At the most optimistic end, heads think it is possible to run meal provision on 1:30, plus kitchen staff and one supervisory teacher. At the expensive end, other heads think 1:8 for infants and 1:15 for juniors are more realistic overall ratios.

Recruiting staff:

All headteachers agree that they do not have existing staff that can be used to deliver a breakfast club. Some express concern that teaching assistants will not want to work from 8am because they are dropping their own children at other schools. Aside from money issues, in certain parts of the country recruiting support staff who can manage large groups of children with a very low number of contractual hours will be a challenge.

Scope of the arrangements that need to be put in place:

Headteachers have listed a number of arrangements that have a cost attached to them. These include administration costs in ordering and managing food delivery, costs of waste disposal and daily cleaning, electricity and heating, ensuring staff have appropriate food safety training and first aid training, finding the physical space to accommodate a large breakfast club in a small school (which has multiple lunch sittings).