Is it proportionate for schools with a good inspection rating to receive inspections the same in length and scope to those received by schools which had exhibited weaknesses in the recent past?

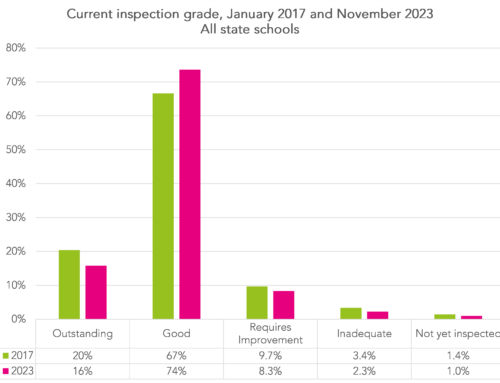

That, in short, was the thinking when new, short inspections for schools with good ratings were introduced by Sir Michael Wilshaw in September 2015.

Ofsted has now launched a consultation on the operation of short inspections [PDF] – so what can we say about how they’ve worked so far?

The detail

It’s worth reminding ourselves briefly how short inspections work.

The purpose of a short inspection, as set out in Ofsted’s inspection handbook is to:

[determine] whether the school continues to provide a good standard of education for the pupils and that safeguarding is effective.

Schools previously rated good receive a short inspection roughly every three years, with the inspection lasting just one day.

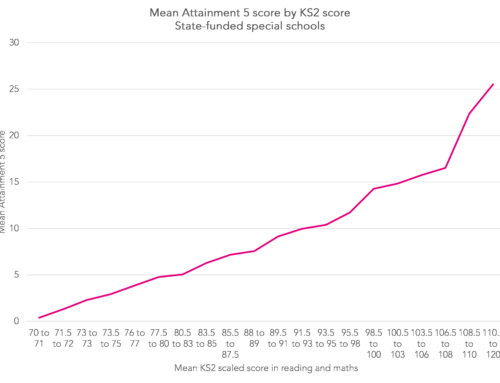

Also subject to short inspections are special schools, nursery schools and alternative provision that have outstanding ratings – unlike mainstream primaries and secondaries that have achieved the top rating, they are not exempt from routine inspection [PDF].

Short inspections don’t change a school’s overall effectiveness grade – rather, one of three things happens:

- the existing, good judgement is confirmed; or

- if there is insufficient evidence for the inspector(s) to satisfy themselves that the school remains good, or if there are concerns about this, the inspection converts to a section 5 inspection; or

- if there is evidence to suggest that the school might be outstanding, the inspection again converts to a section 5 inspection.

(In the case of establishments with outstanding ratings which are subject to short inspections, it is an outstanding rating that is either confirmed, or else the inspection is switched to a full, section 5 inspection.)

The inspection also converts to a section 5 inspection where there are safeguarding concerns.

Where any short inspection converts to being a section 5 inspection, this happens within 48 hours, and generally happens the next day [PDF].

So what can we say from the first 18 months’ operation of the policy? (Figures that are available cover the period September 2015 to March of this year.)

A look at outcomes

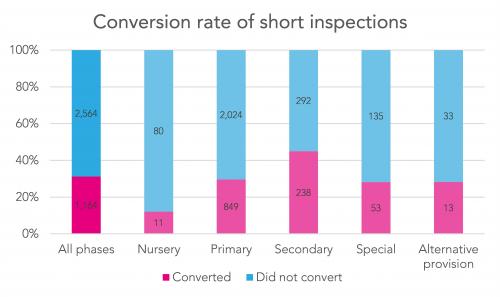

A total of 3,728 short inspections took place in the first 18 months of the policy and, overall, a little less than one in three short inspections – 1,164, or 31% – converted to a full inspection.

But as the chart below shows, the conversion rate is much greater at secondary level than it is for other phases.

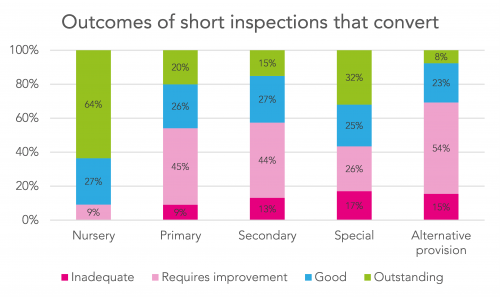

Not all short inspections that convert lead to a rating other than good, however. Among primaries and secondaries, around a quarter (26% and 27% respectively) remain as good after their short inspection converts. And one in five (20%) primaries go up to outstanding after a short inspection, while the equivalent figure for secondaries is 15%.

But the most common outcome when an inspection converts is a drop in rating – 54% of primaries drop to an overall effectiveness rating of either requires improvement or inadequate, as do 57% of secondaries. (And on a quick glance it does seem as if schools with deprived intakes are more likely to drop ratings.)

The chart below shows the full spread of outcomes for short inspections that convert[1]. For nurseries, special schools and alternative provision, it needs to be borne in mind that some of these establishments started off with an outstanding rating, and it is this which the short inspection was seeking to confirm. Care also needs to be taken not to over-interpret the alternative provision figure, as it is based on just 13 short inspections that converted.

Once you take into account the outcomes of short inspections that convert, and those that don’t, 6% of primaries that received a short inspection ended up as outstanding; 78% remained as good; 13% dropped to requires improvement; and 3% dropped to inadequate. For secondaries, the equivalent figures are: 7%/67%/20%/6%.

The consultation

Since shortly after the introduction of the policy there have been suggestions from some working in, and with, schools, that it was placing quite large burdens on them in two ways.

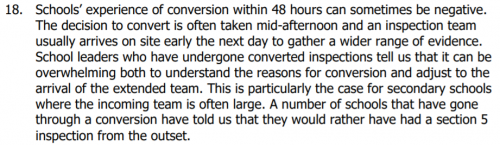

Firstly, in terms of the schools where a short inspection converted to a full inspection. The conversion of an inspection can lead to quite a large team turning up to complete the converted inspection, at short notice.

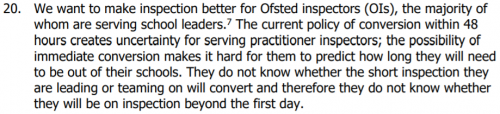

And, secondly, in terms of the people carrying out inspections themselves. Ofsted inspectors, who in many cases are serving school leaders, can also find themselves pulled out of their school – or not – at quite short notice, depending on whether a short inspection converts, causing disruption even if they know provisionally that they are needed.

The consultation document seems to bear out both of these point:

Under the consultation, Ofsted has made two proposals. The first is to extend from 48 hours, to 15 days, the window in which a full inspection takes place after a short inspection converts; the second is to carry out a full, section 5 inspection from the get-go in cases where Ofsted thinks that is necessary[2].

These may help with some of the issues that have been arising, though the proposals have had a mixed response.

But, while the experiences of schools that undergo short inspections aren’t discernible from the data that’s available, given how many short inspections do convert, the proposals are something it’s worth all schools considering.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from Education Datalab? Sign up to our mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive our half-termly newsletter.

1. Data used here excludes the outcomes of two short inspections that didn’t convert, and four that did, which are missing from Ofsted’s data release. The four converted short inspections were more likely to have resulted in inadequate judgements [PDF] than is typically the case.

2. For the former of these proposals, the 48-hour window would remain for inspections that convert as a result of safeguarding issues. The latter of these proposals would not apply to good and outstanding nurseries, special schools and alternative provision [PDF].

It seems crackers if Ofsted were sending inspectors in for a short inspection if the data didn’t suggest that the school was still good – what a waste of resources and disruption for the schools! Sure, there will always be cases where the data is consistent with remaining as good, but inspectors will have second thoughts when they get into the school, but it looks like there must be plenty of scope for reducing wasted time and energy by picking up schools where the data is dodgy before the inspectors get there.