This is the first in a series of posts on the education white paper. The other parts can be found here.

It has been just over a month since Educational Excellence Everywhere – the government’s education white paper – was published.

In a document that covers topics ranging from teacher training to school funding, unsurprisingly the greatest amount of attention has been paid to the proposal that all schools will be required to become academies by 2022, or earlier.

While in some sense a continuation along a path already being followed, it’s worth considering a couple of things to get a sense of scale, so that we can understand quite how significant or otherwise the plan set out in the white paper is.

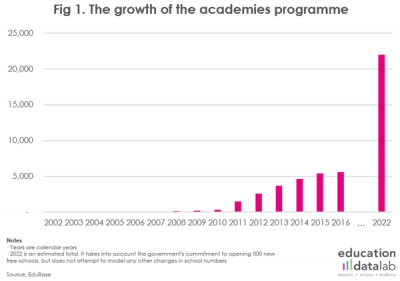

Charting the total number of open academies, the first thing that becomes clear is the change in scale between the early years of the academies programme – when, up until September 2008, there were still fewer than 100 such schools – and the period since 2010, when the Coalition government allowed high-performing schools to voluntarily convert to academy status.

The second thing that’s clear is that there is also a difference in scale between the current situation, and the picture that will exist in 2022, if all school have become academies.

In short, this is a major reform.

Regional variation

Looking at the data, a few other things become clear.

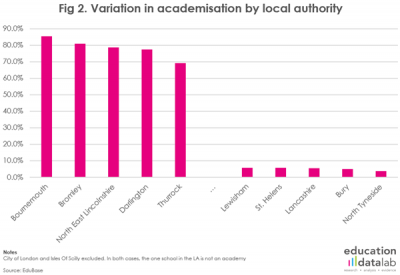

Firstly, the proportion of schools which have become academies varies markedly around the country. At one extreme, more than 80 per cent of the schools in Bournemouth and Bromley are academies. At the other end of the scale, less than five percent of the schools in north Tyneside and Bury are academies.

Looked at in map form, a number of things become clear.

Most noticeable are the large parts of the north, where very little of the system is academised.

Also of interest, though, is the huge variation in how much London boroughs have embraced academisation.

Looked at in this way, the existence of a region in the south of the country where few schools have become academies also becomes clear.

Academy trusts and scale

Academy trusts – the bodies which run academies – feature frequently in the white paper, and are also worthy of some thought. The availability of enough academy trust capacity is something we’ll return to in a later post, but there are a couple of points worth making briefly.

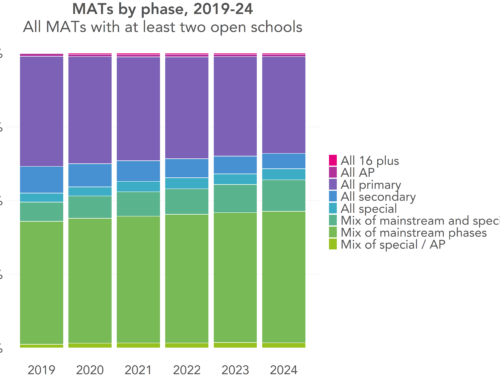

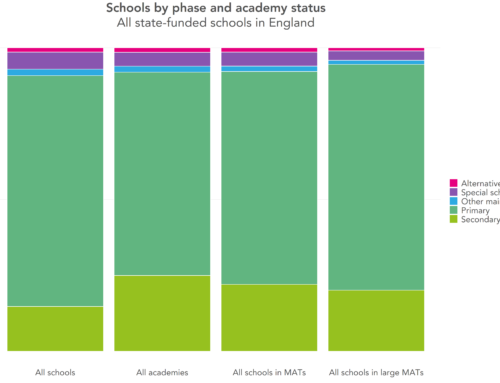

The white paper sets out the government’s expectation that most schools will join, or set up, multi-academy trusts (MATs).

As Mike Cameron has suggested, the growth of the MAT model is likely to happen as schools seek to gain economies of scale – at a time of tight funding, banding together in this way might seem an attractive way to try to keep costs down.

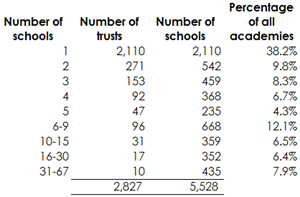

Looking at the data, we currently find that by far the most common situation is for an academy to be in a trust on its own – 38 per cent of academies are in this situation[1][2].

And among schools that are not in standalone trusts, the most common situation is for an academy to be in a trust with only one other school.

The white paper sets out the government’s view that more trusts of 10-15 will come into being in the coming years:

We know that on average MATs can begin to fully develop the centralised systems and functions that will deliver these benefits at a size of around 10-15 academies – although the real determinant of effective size is the number of pupils. Over time we expect there to be many more MATs of this size…

At present, though, there are only 31 trusts in this bracket, making up around one in fifteen academies. And there are only 27 trusts with more than 15 schools in them, in total accounting for around on in seven academies.

Looking ahead

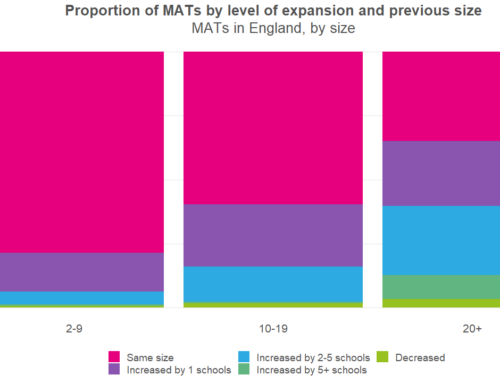

Taking the longer view, it will be unsurprising if MATs continue to grow.

At the minute, even the largest trust, Academies Enterprise Trust (AET), only has 67 academies – 1.2 per cent of the entire body of schools that are academies.

While there are factors besides economies of scale which will determine the size to which the typical academy trust grows, and which in some cases will work against the growth of very large MATs – to date, it is some of the largest chains such as AET which have got into trouble and been forced to hand over schools to other trusts – it is likely there will come a point in the future where even the largest academy trust that exists at present looks small.

1. A total of 102 schools feature in EduBase without trust or sponsor information. While most of these are likely to be in single academy trusts, they have been excluded from this part of our analysis.

2. A loose definition of trust membership has been adopted. Academies Enterprise Trust (AET) runs 62 schools in its own name, for example. A further four schools are part of the London Academies Enterprise Trust, and one school is part of the Unity City Academy Trust. The Department for Education considers AET to be the sponsor of all 67 academies, so for the purposes of this analysis, the schools have all been considered to be part of the same trust.

[…] This is the second in a series of posts on the education white paper. The other parts can be found here. […]